The 1874 Recorder notice is the earliest newspaper clipping I can find about Herbert M. Blanchard, my first cousin, three times removed. In between that clipping and a later, final headline, “CAREER OF CRIME ENDED,” lies situated a brief and largely forgotten life, preserved in a tantalizing coating of lies and legend.

Herbert Blanchard ambushed me in the summer of 2024, thanks to a surprise discovery I made while cleaning my basement. It was a lost artifact, a not-quite-obsolete external hard drive containing numerous files that I’d assumed lost over the years, victims of my moving to new locations, new interests, new computer operating systems and means of storage. I’d long regretted the loss of a massive body of genealogical notes that I’d compiled in the 1990s, when I had studied my family history with the kind of obsessive energy only available to those with flexible schedules and no children.

In retrospect, it was providence that put that hobby on hold because it’s a far, far easier avocation now, in many regards. Genealogical research had once required schlepping to libraries, town halls and cemeteries in years past. At best, I could send away for rolls of microfilm on loan from the Mormon Church’s Family Research Center in Salt Lake City, and sit in an LDS church basement in Amherst and wind through the scans. I can now access much of that same information (mostly), free of charge (mostly), sitting comfortably at home in my boxer shorts.

So in the summer of 2024, I resumed studying my family history, piecemeal, on the internet. I have long focused primarily on my father’s family, the Sweets, largely inspired by my late father’s admonition that his family could not be traced past the Civil War. Respectfully, Dad, I think nobody telling you that was trying very hard: researching this family has been fairly easy pickings, as they have just about stayed put in a fairly well-documented part of the country, for generations.

But even tracking down the histories of subsistence farmers in Massachusetts will have its obstacles. Trails do run cold, records fail, names are forgotten, people with lingering feuds cut ties.

Gratefully, the skills that I developed in my two decades as a newspaper reporter often parallel, intertwine and augment those of a genealogist. Lessons learned in my vocation and avocation have routinely lifted both sets of skills.

One simple lesson has been that there are times for diligent focus on a particular source, and then there are times you close your eyes and stick a pin in a map. To twist the words of my sixth cousin, three times removed, not only should we “tell all the truth but tell it slant,” but we should also be compelled, when looking to find the truth, to think at an angle. I’ve found that the best way, when stymied in a search, is to search sideways. Dig around the hole where you thought the treasure was. Turn the paper over to find the meaning. In the case of genealogy, look at the siblings, and if that fails, look at the cousins. Stare at a completely irrelevant-looking detail with your one good eye, like Columbo.

If your family tree is, like mine, an absolute marsh of men with the same name, pick out a sibling or a spouse with an odd name, like Sarepta, Romanzo, Benoni, Wanton, or Remember. And go.

Such has been the case as I put together the story of my great-great-grandfather Elijah B. Sweet (1839-1907), Civil War veteran: son of William, grandson of William, father of Ernest, and grandfather of Ernest. Great-grandfather of William, and great-great-grandfather of William, me.

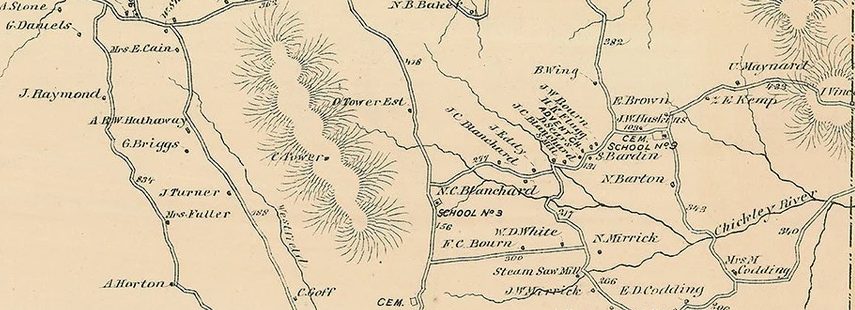

While tracking down Elijah’s siblings, I was surprised and delighted to stumble across a detailed and lurid account of his nephew Herbert Blanchard, whose story brought brief infamy to a remote corner of Berkshire County, Massachusetts, in the tiny town of Savoy.

While most of my family research looks like a tally sheet of census records, property transfers, and birth and death certificates, my sojourn into this branch of the tree bared a saucy little trove of newspaper accounts which read like some lost Wild West yarn. Every time I’d peel away a layer of this story, there would lay another story, beckoning. Every time I tipped my spade into a lie, there would be glimmering nuggets of truth.

Briefly: Herbert M. Blanchard (b. 1852), the only child of Mary Jane Sweet, became momentarily notorious for shooting the father and uncle of a 14-year-old girl whom he desired to claim as his third wife. A girl who was a cousin of his first wife, also named Blanchard, and a cousin of his actual third wife. He would be branded a double-murderer in newspapers throughout the country, though both the men he shot would outlive him by several years.

As it turned out, that shooting was just the beginning of a rapid and precipitous descent for Herbert M. Blanchard. Ultimately, though, it wasn’t his rage that made for his undoing. Rather, he may have loved just a little too much, and he definitely loved too many.

Leave a comment