Continued from Part Two

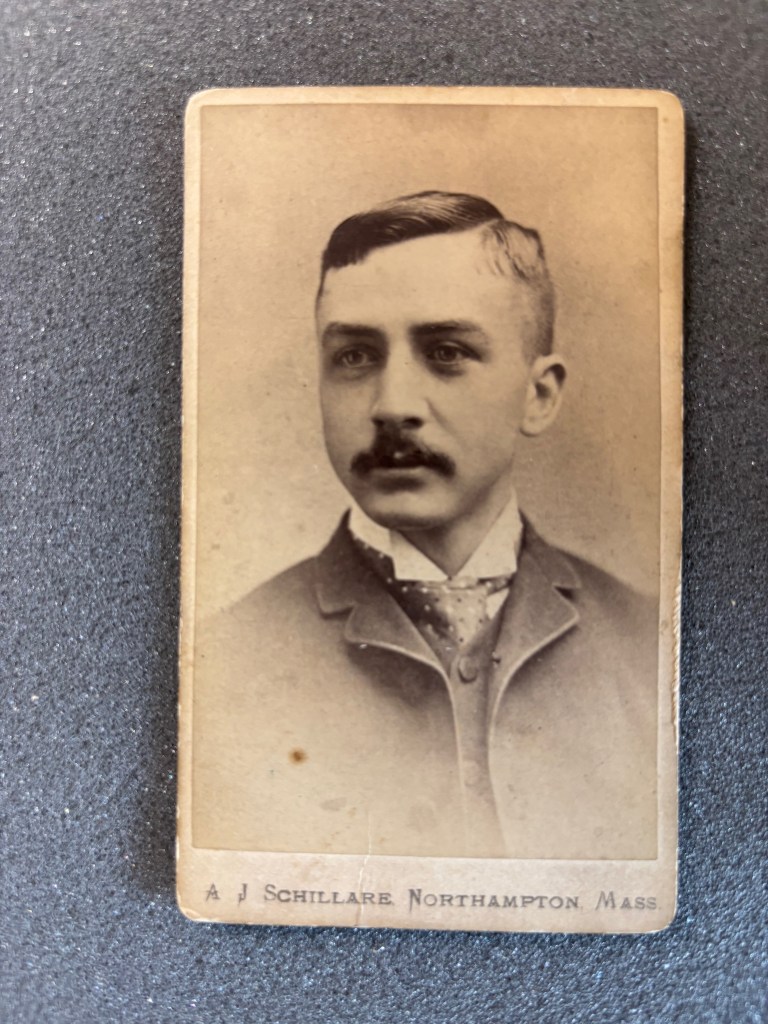

Less than a dozen of the photographs in Benson Munyan’s collection of mug shots are of criminals Munyan actually logged himself, crimes of finance and of blood, arrested with varying degrees of success. Most of these rogues were photographed by Québécois Amand Joseph Schillare, who operated out of studios on Main Street in Northampton, near the county courthouse. “A.J.” Schillare had taken up the trade of photography after his job at the Nonotuck Silk Mill (where he had worked since the age of nine) washed away with the flood of 1874.

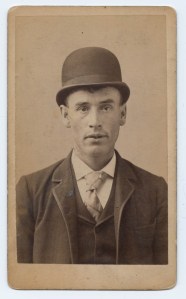

There’s William O. Taylor of Wendell, curls just peeking out from under his tilted hat, not looking quite straight at the camera, at least with one eye. He was arrested in 1886 with Frederick “Monkey” Pratt of Shutesbury in connection with a trio of burglaries at boarding houses in Ashfield. He entered a not guilty plea and ended up in jail for two years. Seeing this, Pratt retracted his not guilty plea and was released on bail pending sentence. That release was brief, as Pratt was back in custody after hitting a J.H. Williams of Leverett over the head with a stone jug of cider soon after leaving the Greenfield courthouse, knocking him out.

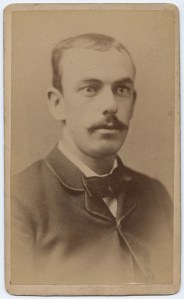

Munyan kept a photograph of Philadelphia-born Edward Cohen, a traveling salesman for Northampton’s Smith Carr Bakery Company, manufacturers and wholesale dealers in crackers and biscuits, for nibbling off more than he could chew of the company’s coffers. The 20-year-old Cohen was sentenced in 1888 to an undisclosed term at the state reformatory for the undisclosed amount of embezzlement.

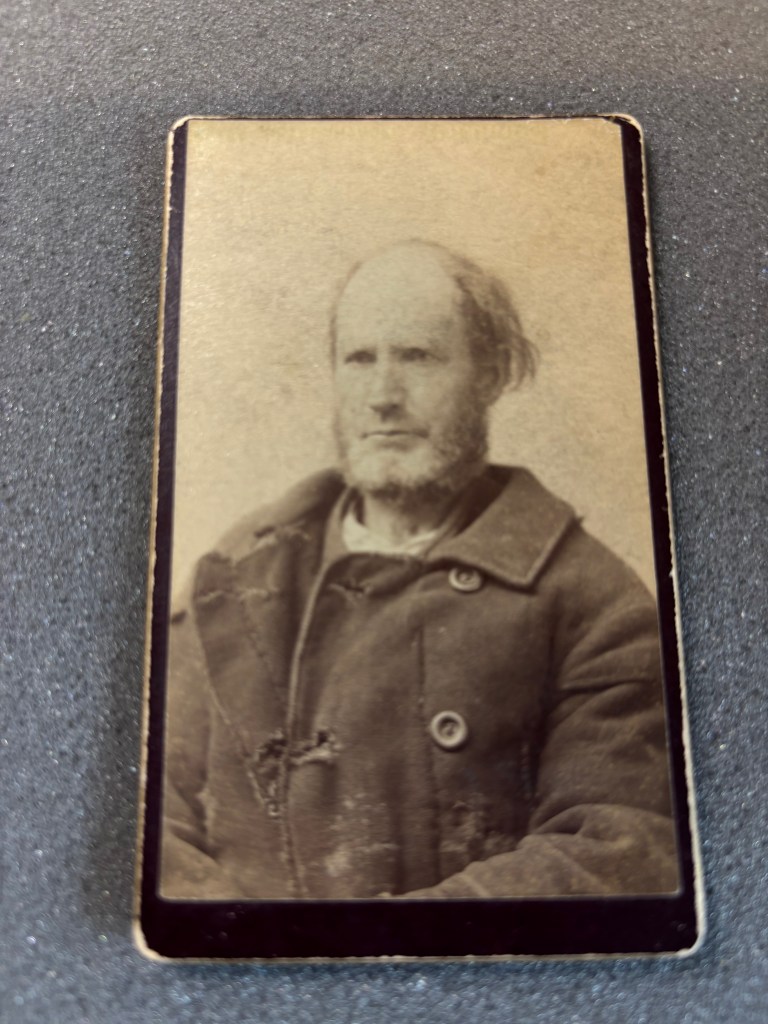

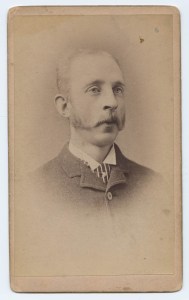

There’s the tired-looking Charles Miller, an illiterate and unemployed wood chopper, of whom Munyan writes in his comments merely “French,” 1889 thief of buggy and harness. Also, Pittsfield native Benjamin F. Wilson, bearded, balding, and bedraggled in his frayed peacoat, 64, a sneak thief by trade. A hardened criminal with already three jail terms under his belt, including one for stealing copper from the brass works in Munyan’s hometown. He was convicted of breaking into Horace Williams’ barn in Westhampton, earning an extensive prison term as a repeat offender.

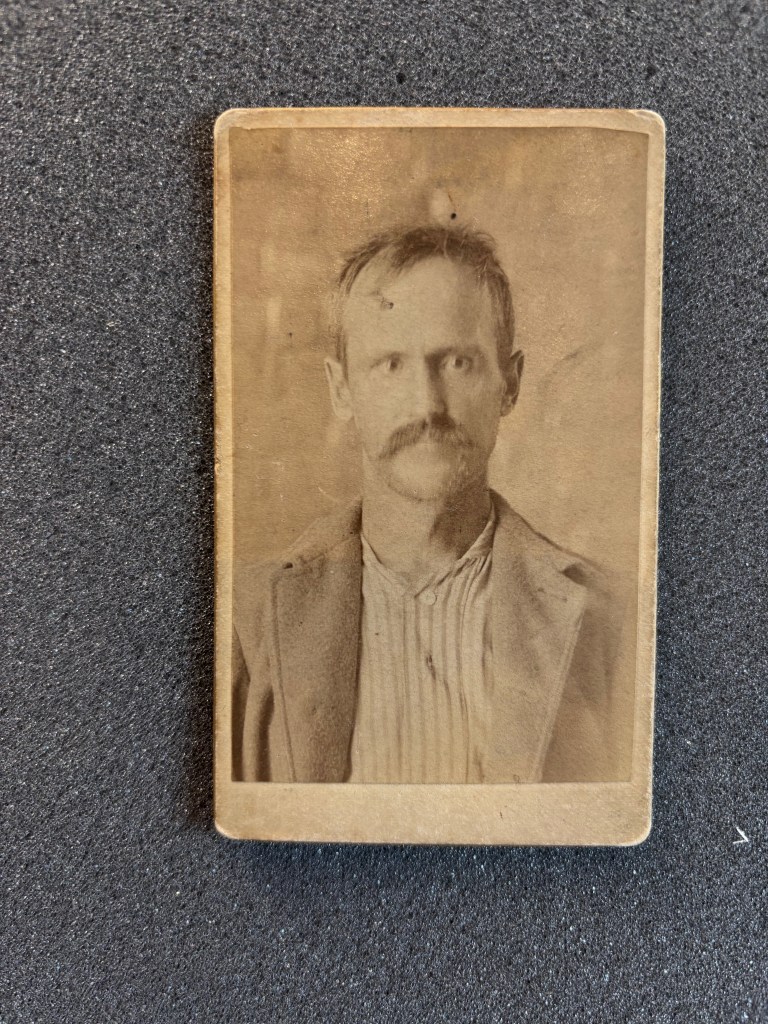

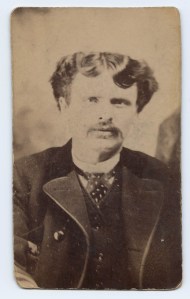

The piercing yet enigmatic gaze of Lucius Ezra Fisher Hatstat of Erving stays with you as you flip over the card to read Munyan’s inscription of the crime alleged: incest. Hatstat’s wife, Laura, who had since filed for divorce, alleged the New Salem-born laborer had perpetrated the crime upon his daughter, Alma Geneva, in November of 1887, when she was 14.

The daughter, described by the Springfield Daily Republican as “a weak-minded child, who had to tell her pitiful story before a crowded courtroom,” failed to convince the jury, and Hatstat was acquitted in August 1888. Laura Hatstat was in turn charged with adultery for taking up with Northfield resident Emery White, who was married to Lucius Hatstat’s sister Millie. In 1890 Mr. White would marry not Laura Hatstat but none other than her daughter Alma Geneva Hatstat. The girl had turned 18, twenty years White’s junior. That marriage didn’t last, and Alma married a George Sampson (fifteen years her junior) in 1911, the year that Lucius Hatstat died of what would later be known as Parkinson’s Disease.

Too Many Wives

Switching back briefly to photos from the collection that weren’t necessarily Munyan’s own cases (but for one), the gallery also noticeably features those especially Gilded Age criminals, criminals who violated their marriage vows to various and increasing degrees. There’s Percy St. Clair, 28, a piano salesman who absconded from Lynn in 1892 with his 16-year-old clerk Bertha Colomy in tow and a pocket full of cash stolen from the piano shop. St. Clair penned a long letter to his wife remaining in Lynn while holding out in Buffalo, New York, and later Detroit, going by the alias Howard E. Thornton. The law caught up with Percy, but though he was charged with adultery, he was sentenced to four years in prison for the larceny alone. Adulterers Clarence Allen Scott and Martin E. Lesner got to share their shame for the camera as well.

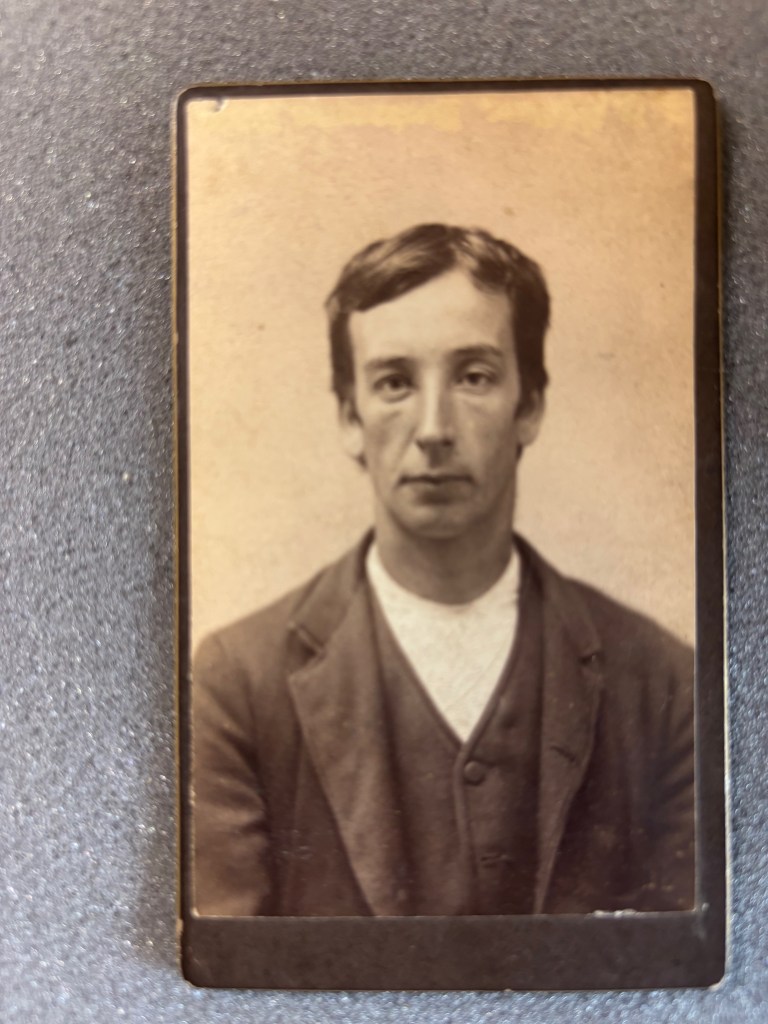

Louis F. Johnson of Lawrence stood before the camera in 1888 because of his marriage to a Miss Tina Gerring the previous year. He had told Tina that he was waiting upon an estate settlement that would make them $19,000 richer, but in the meantime, he borrowed $700 from her brother, which went towards frequent visits to New York, and then the letter appeared from his other wife.

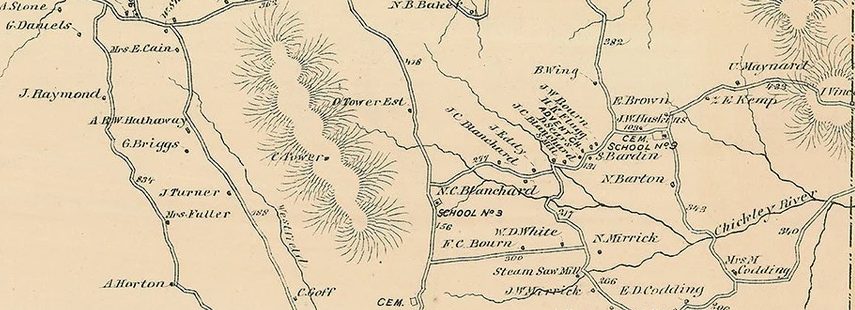

Rounding out the group of these lovers is my cousin, Herbert M. Blanchard, about whom there’s enough to fill a book, and I am doing just that, so more about him later.

To Be Continued: Munyan’s Murders.

Photo Credit: All the photographs shown here were made available courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the nation’s oldest historical society, which maintains an independent research library in Boston’s Back Bay. You can now view the entire Munyan collection at the MHS website, where you can support the museum through the purchase of high-definition scans of the criminals of your choice.

Leave a comment