Continued from Part Three

As mentioned in a previous post, there are a number of killers in Benson Munyan’s rogues gallery from cases that he did not personally investigate, including a few in the western district that he oversaw.

For example, there is Charles E. Adams, sentenced to twelve years of hard labor at Charlestown for the January 1892 stabbing death of Louis Laussier, a 20-year-old French-Canadian blacksmith. At a grand concert and ball for the Black community of the Lenox village of Lenox Dale, what started with Laussier, an amateur boxer, good-naturedly showing off his boxing skills, turned ugly. It appeared that Laussier sustained a minor cut to the chest in an ensuing scuffle with Adams and other attendees, but when the Canadian expired the next day, an autopsy revealed a knife blade embedded in his heart. Adams, a native of Syracuse, New York, staying with fiddler and string band leader Billy Van Allen, was promptly charged and eventually convinced to plead guilty, earning him an escape from the gallows.

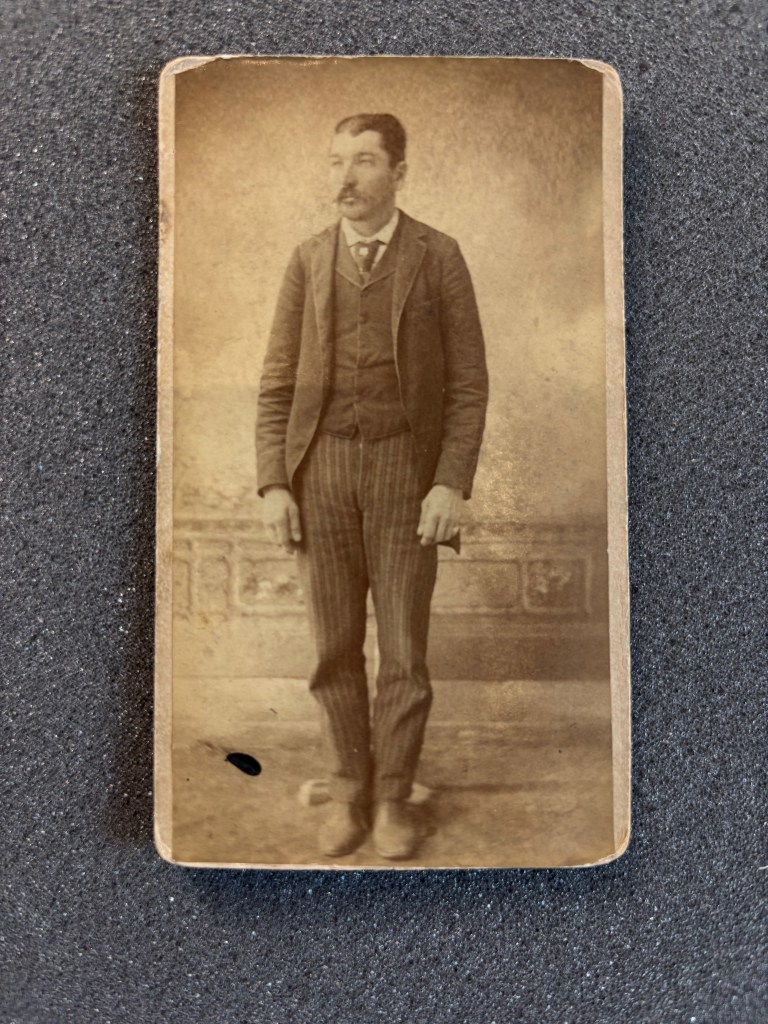

But probably the most infamous murder case from Munyan’s jurisdiction in the Commonwealth (though not his actual collar) was William Coy, 35, the last man to be hanged in Pittsfield, and the first white one. The grey-eyed, large-handed Coy looks fairly dapper, something quite distant from the farmer’s hovel in Washington, Mass., where he had axed, slashed, and dismembered former streetcar driver John Whalen in late August of 1891.

Coy’s fate was sealed on October 13, 1891, when Washington Selectman A.B. Pomeroy’s dog smelled something bad in the woods, digging out a man’s suspender that resisted removal from the ground. They were attached to the mutilated remains of John Whalen, his head bashed in, nearly decapitated, his face demolished. His legs, which had been savagely hacked off above the knees, were found on top of the body.

The community was horrified. Not since would-be gold miner Oscar Beckwith of Austerlitz, New York had murdered, butchered, and allegedly eaten his business partner in 1882, or more recently and closer, Fred Hale of Hinsdale had beaten his brother William Henry to death with a whiffletree the previous year, had the newsreading public in Berkshire been this alarmed.

The investigation revealed a domestic drama at the center of the butchery. Whalen, then working for the Boston and Albany Railroad, had been boarding in a ramshackle house in Washington with Coy, Coy’s young wife Frances, and her two sons from a previous marriage.

On that late August night, co-workers Whalen and Coy had taken a trainride to Pittsfield and Westfield, stopping at several saloons on the way. A loose-lipped Whalen had drunkenly confessed to bedding Mrs. Coy, and that they planned to elope to Kansas. Confirming this scenario in Coy’s mind, his wife had told him that she was planning a trip to visit her relatives.

After stewing in solitude about this news on the train back to Washington, Coy returned to the hovel, where he discovered a trunk packed with his wife’s clothes and Whalen’s. Enraged, Coy took an axe to the sleeping Whalen, later hacking off his victim’s legs when the corpse proved too heavy to carry away in one piece.

The investigation wrapped up fairly cleanly when deputy sheriffs Charles Cutting and Moses Pease found Coy in possession of $150 and a gold watch belonging to Whalen. At first claiming the valuables were Whalen’s payment for Mrs. Coy’s favors, Coy broke down and confessed to the murder, though he claimed it came in self-defense after a struggle.

“For if I hadn’t killed him, he would have killed me,” Coy later said. “The question was who would get the ax first and who was the drunkest.”

It took less than a week to try and sentence Coy for first-degree murder, though, thanks to two stays of execution, it would be another year before Coy stood before 300 spectators in the county jail’s courtyard and had the rope tied around his neck. His belly full of a final breakfast of beefsteak, ham and eggs, bread and butter, and fried potatoes, Coy maintained a calm demeanor. The hangman assured him that the noose would be tight and there would be no “bungling” of his execution.

“All right,” were Coy’s last words, apart from a final whispered goodbye. And it was: spectators reported that this hanging was “one of the most successful on record in the country.”

Munyan’s Murderers

Three distinct types of killers are represented in the collection of portraits of murderers in the carte de visite of Munyan’s own cases. The innocent, the tragic, and the depraved.

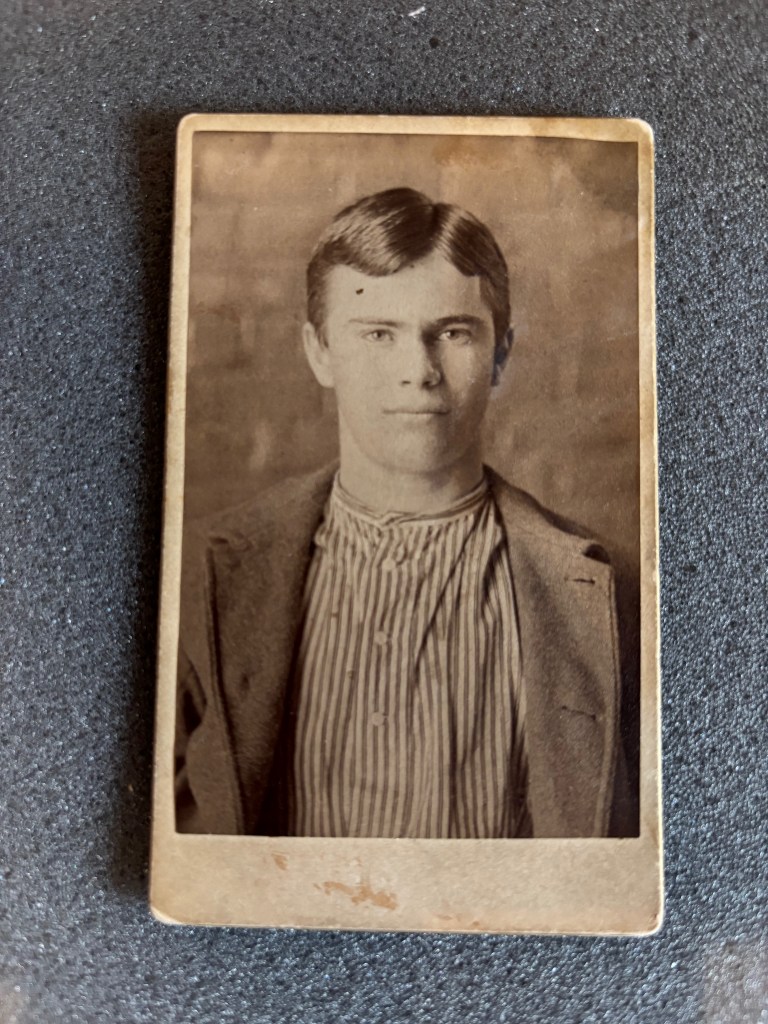

Lincoln J. Randall

Stout and boyish, with dark hair carefully combed for posterity, eighteen-year-old Lincoln J. Randall did not quite fit the expected portrait of someone who would blow his father’s brains out, as Lincoln allegedly did on November 29, 1887, in the Montague home of David Marcus Randall.

The supper dishes had been cleared after 5 p.m., and the family gathered in the living room, all except “Linny,” David’s only son, who’d ducked out shortly before the meal’s end on an errand in the nearby village of Montague City.

Merchant David Randall was regaling his family with one of his reputably enhanced tales, this time about his day’s work, buying eggs from local farmers to sell at local markets, uttering the last words he would recite in his life: “I bought those eggs for 15 cents a dozen, and—”

There was a bang as the room fell into darkness, the lamp overhead extinguished, and Randall’s words replaced by the sounds of shattering glass.

What had been thought to have been the result of an exploding lamp turned out to be something wholly more grim when the room was illumined again and the scene revealed: buckshot embedded in the ceiling and walls, a window shattered and blackened by powder, and the prone form of David Randall, the back of his head blown entirely off.

Shock ensued, as was the search to find the killer, who had clearly fired at close range, steadying the weapon on a dove coop that stood on the home’s piazza. Lincoln was found where he’d said he’d gone, near the post office and store in Montague City. He expressed a lack of surprise about an exploding lamp—which had been the cause cited when the messenger was sent out—but sorrow at the news of his father’s grisly death.

The next morning, with the family at a neighbor’s and David Randall’s corpse being prepared for burial in Adams, Munyan went to work. He quickly found a musket in the woods near the home, a throwing distance from the road. Investigators also found an old pipe with lead scraped from it, apparently to manufacture the shot. Munyan took a walk to Turners Falls with Lincoln in tow, peppering the youth with questions. With a single donut in his belly from breakfast, Lincoln J. Randall would accompany the detective to Greenfield, where he would spend two years waiting to have his day in court.

The murder and the trial were a sensation in the papers, with distractions such as Randall’s spiritualist aunt and intimations that the elder Randall’s medicine may have been tampered with and that a druggist hired the real killer to cover up a mistake in the dead man’s prescription. But it all came to naught: in the spring of 1890, the jury acquitted Linny after deliberating for 40 minutes. The only apparent motive the prosecution could land on was that he’d been engaged to a Turners Falls girl and that the $1000 insurance on his father’s life would make a sweet dowry. It simply wasn’t convincing.

Lincoln’s innocence established, he relocated to Holyoke and in 1891 married nineteen-year-old domestic servant Maria Murphy, an Irish immigrant. She died suddenly four years later of an unclear cause believed to be apoplexy. He married another nineteen-year-old Irish immigrant the following year, this time weaver Mary Sullivan. They later relocated to Springfield. In August 1931, Lincoln, 61, was bicycling home from work when he was struck by a car and later died of his injuries.

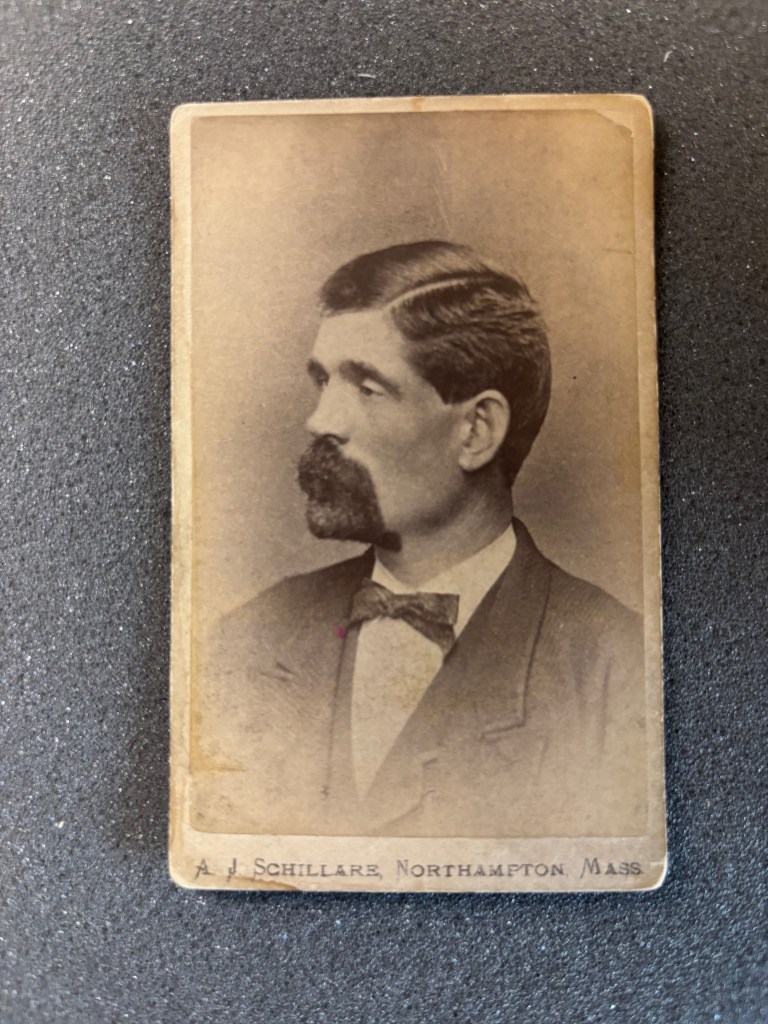

Eugene Samuel Taylor

Schillare’s surviving 1886 portrait of Greenfield farmhand Eugene Samuel Taylor shows him mostly in profile, gazing apparently sadly to the photographer’s left, sporting a walrus mustache and a bow tie. Perhaps it is from hindsight that I divine sadness from his lidded eyes and ample brow, knowing Taylor murdered his two-year-old son with strychnine concealed in coconut candy.

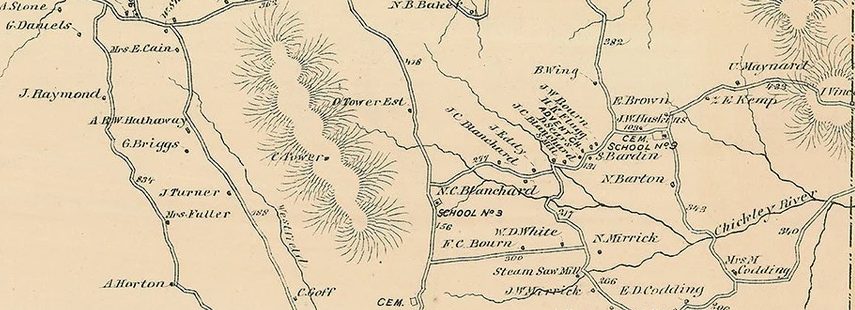

The Vermont-born Taylor, who lived in a cottage along the meadows just north of Deerfield Academy, had been working for Deerfield farms for about 15 years but had fallen into a funk after financial troubles had accelerated an already souring marriage.

Taylor had leased some land on a crop-share basis, and his tobacco crop was coming in poorly. He owed his brother-in-law $1,000, and his wife had paid off many of the family’s expenses working as a dressmaker. With creditors still after her for the ring purchased for her wedding in Mooers, New York, four years previous, the former Susan Jane McDowell was after Eugene to contribute more to the family, a sentiment her mother shared.

Not a man to share his feelings with others, Taylor would stew in his worries and gloom until May 19, 1886, when he walked into the Greenfield apothecary shop of Francis Bacon Wells and asked for something he could use to put down a troublesome dog.

“Oh, he’s an ugly fellow, and weighs 125 pounds,” Taylor said when Wells asked how big a dog he wanted to kill. The druggist promptly prepared two 2.5-grain doses of strychnine.

According to his later testimony, Taylor’s intention had been suicide, over his troubles and affronts: “I think it’s about time for a man to die when he comes into a house for a week and not have his wife notice him, no more than a dog.”

But whether it was a plan or opportunity, his suicide attempt included the murder of his little son, George Eugene Taylor.

“See candy Papa gave!” the child told his mother the next evening.

“Papa never buys candy unless Mama asks him,” Susan Taylor said as she worked on a dress. But the child showed her the ball of candy, and she thought nothing more of it until the convulsions started. Taylor had indeed given his son candy, laced with a little over a grain of the poison, and Taylor had taken twice that dose himself. By the time the physician came, Georgie’s sufferings had ceased, the body too rigid to even place the arms in the proper repose of death. Taylor had to be knocked out with morphine because he fought taking the emetic.

As an uncommunicative Taylor sat in a Greenfield cell awaiting prosecution, his neck healing from another botched suicide attempt—slicing at his neck with a knife as the authorities came—his legal representatives were preparing an insanity defense, citing stories of madness in the family. Stories were that his mother, Orilla Choate Taylor, had been considered partially insane since before his birth, though she’d never been treated for such. A brother, Francis E. Taylor, had committed suicide in 1860 while boarding at the Revere House in Brattleboro, Vermont. He had taken a dose of strychnine, disconsolate that illness had left him unable to pursue work for the previous two years.

Munyan hunted down these stories, and after returning from Wardsboro, Vermont, where he had interviewed Taylor’s 88-year-old father and investigated Taylor’s other ten siblings, concluded there were no grounds to honor an insanity plea.

Eventually—prosecution was delayed and the grand jury reconvened because the original indictment misspelled “strychnine”—Taylor pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life at the state prison. He unsuccessfully petitioned for a pardon in 1904 and died three years later from tuberculosis and was buried in Concord Reformatory Cemetery.

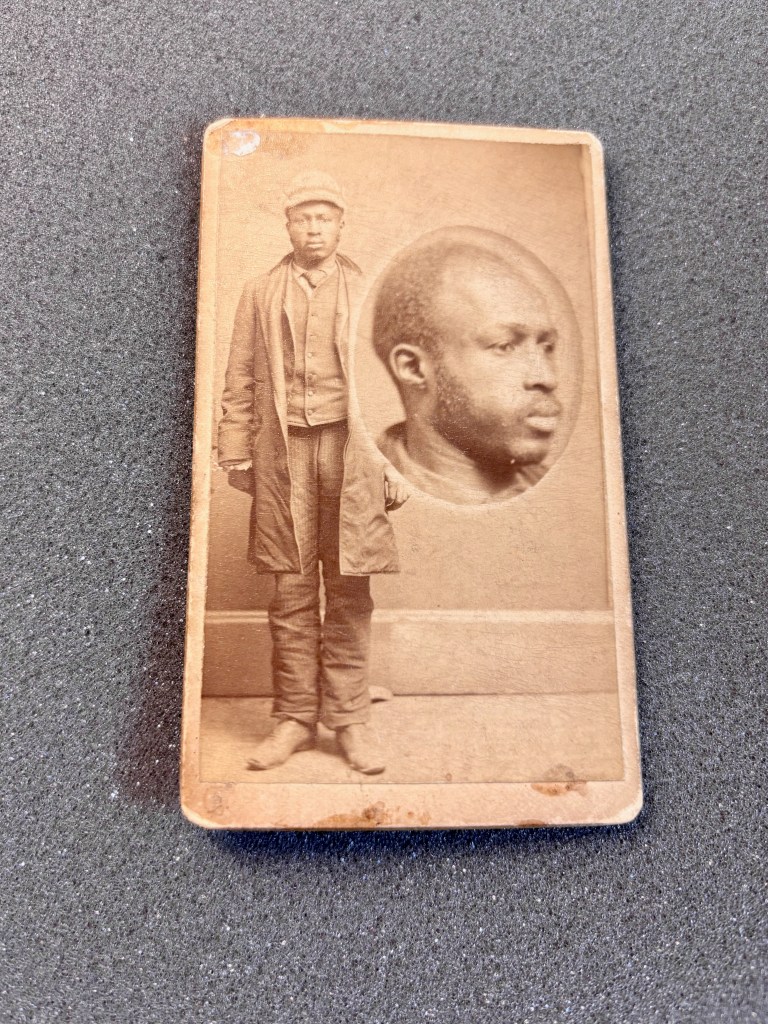

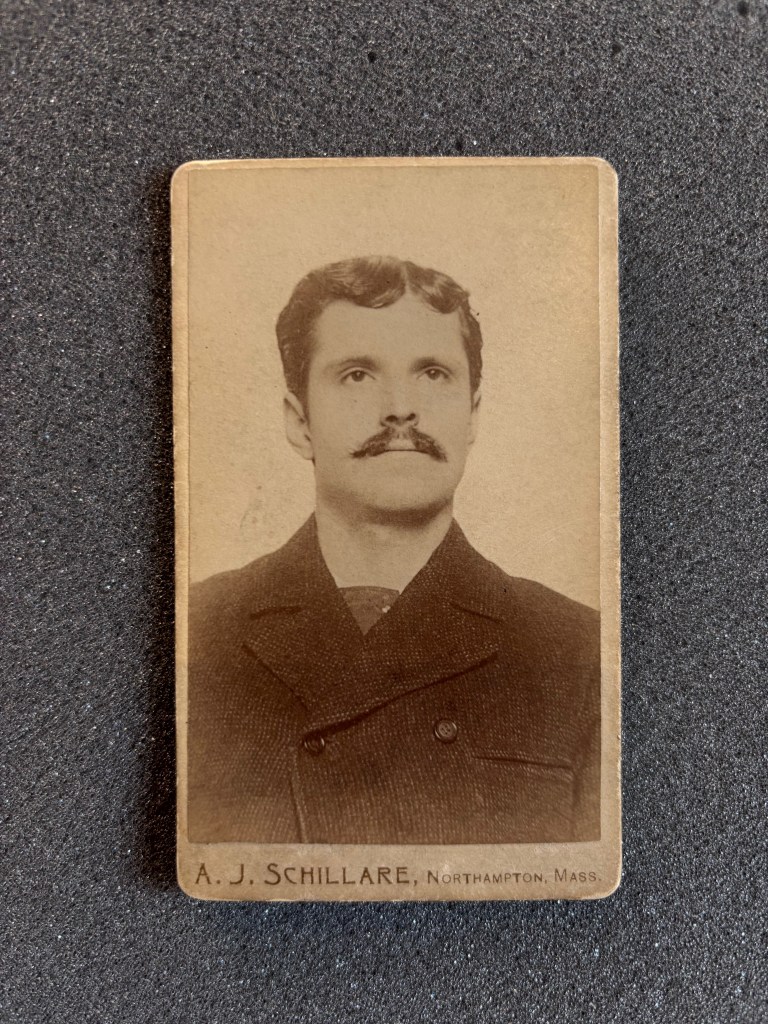

Edward Begor

Appearing freshly groomed in his peacoat and looking like he is staring off into the sunset, Edward Begor seems more peaceful than he deserves to be. Begor (also known as Beauregard), a French-Canadian sawmill worker, was sentenced to life imprisonment for the scandalous 1892 murder of Abigail Rogers, an impoverished 55-year-old woman who was living on both the literal and figurative edge of society, in a hillside hovel near the Farley Road railroad station in Wendell, Mass. Rogers worked summers as a berry picker and the rest of the year in the Farleyville knitting factory, but locals had whispered about her unsavory reputation.

Rogers’ body was discovered in her shack, some four days after her death in September 1892, covered in a pile of bedclothes and rags, her head marked with three killing wounds. Begor, a resident of nearby Orange, was soon arrested, based on testimony that he and some younger men had been seen at the shanty.

Begor might have walked if not for his own big mouth. Begor’s defense counsel had actually gathered sufficient evidence that might have secured his acquittal. However, Begor sealed his fate when he decided to open up to fellow inmate William O. Taylor (possibly the previously mentioned Ashfield burglar and associate of Mr. Monkey Pratt), whom Begor had come to know while in the pokey for a previous larceny. Begor had let slip some details of the crime and had even gone so far as to ask Taylor to help him escape by smuggling in the right tools into the jail. Later, Begor took ill with cramps, and his friend was allowed to attend to him. Begor opened up even more to his nurse, confessing that the murder came as the result of a drinking spree by Begor and a pair of younger friends, who knew of Rogers’ shack as a place to go for more drinks, a meal, and the companionship of the woman who “would execute a skirt dance with exceedingly limited skirts.”

The three spent the night, and the drinking resumed Sunday morning, but by this time Begor had sent his friends on their way, to their relief. The bender turned ugly when Rogers refused Begor’s advances. First with his fists and then with an iron skillet, Begor struck the woman over the head. He attempted to rifle the shanty for what money she had, some $40, but seeing that she was still stirring, he finished her off with a club from the woodpile, covered the body, and fled.

It was a shocking and thrilling tale for Taylor to hear, and even more so for Munyan, who had situated himself right outside Begor’s cell, taking note of every detail, as per arrangement with Taylor. This revelation turned the case around. Begor retracted his not guilty plea, opting for a plea of guilty to murder in the second degree.

To Be Continued: The Case That Broke Benson Munyan.

Photo Credit: All the photographs shown here were made available courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the nation’s oldest historical society, which maintains an independent research library in Boston’s Back Bay. You can now view the entire Munyan collection at the MHS website, where you can support the museum through the purchase of high-definition scans of the criminals of your choice.

Leave a comment