Continued from Part Four

Detective Benson Munyan continued pounding the beat of the Northwest district for close to six years after collaring Herbert Blanchard. The 1890s saw Munyan called out to an impoverished and violent section of Hatfield, for cases that he opted to leave his camera unused.

The Cahill Case

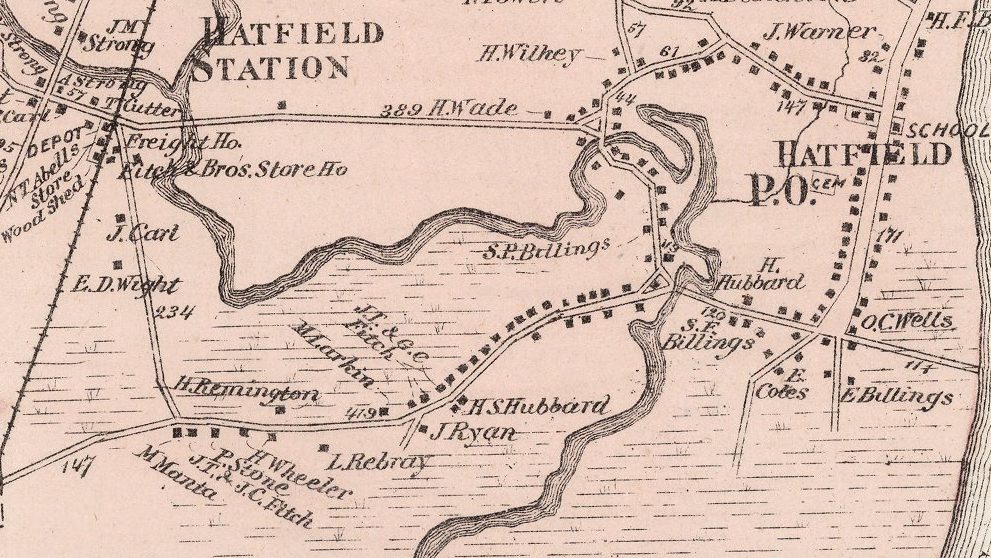

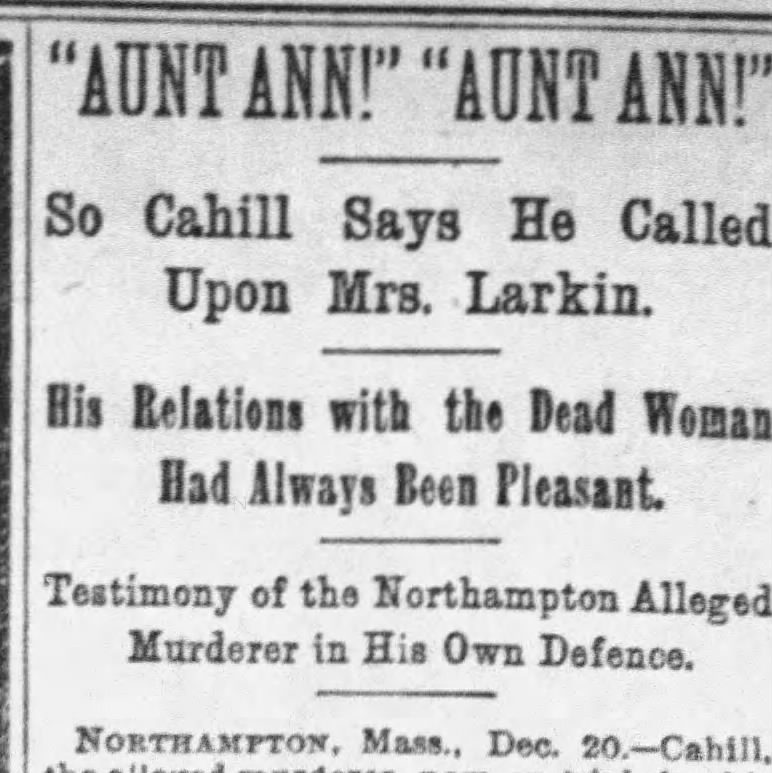

In June 1892, Ann Larkin, 75, was found dead seated in a chair at home, a bullet hole above her left eye. She had been killed in the farmhouse that she shared with the family of Daniel Cahill, the husband of Larkin’s niece. Cahill, who had been seen leaving the house shortly before the shooting, and subsequently disappeared into the surrounding woods, quickly became the prime suspect.

Munyan gathered evidence and led efforts to scour the dense terrain around this remote section of Hatfield, unfortunately dubbed with a racial slur after the concentration of rural Black families who had settled there. Cahill was eventually spotted at his barn, where a neighbor urged him to surrender. Although he initially brandished a revolver and threatened suicide, Cahill ultimately walked into the Northampton jail, asking for protection. At trial, the prosecution argued that Cahill had murdered Larkin over a dispute about inheritance, and Munyan provided circumstantial evidence such as a pair of overalls worn during the shooting, the jury was swayed to acquittal by Cahill’s testimony arguing the shooting was accidental.

The Fighting Wheelers

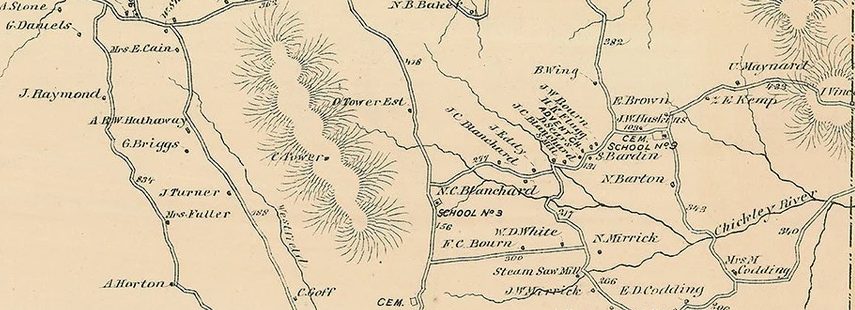

Just months after the Cahill acquittal, Detective Munyan returned to the neighborhood after Jared Remington, 74, was arrested for the fatal beating of his nephew, Richard Wheeler, 35. Reportedly, a fight had broken out when an inebriated Remington accused Wheeler of stealing whiskey he had brought home from Northampton. According to witnesses, Wheeler chased Remington out of their hut, grabbed a wooden bar used for barricading the door, and threatened to kill him. Wheeler reportedly hit Remington several times before Remington took the club from him and struck Wheeler on the head with such force that the weapon splintered. Wheeler survived several days but ultimately died from his injuries. Munyan worked up a case for the state, summoning twenty witnesses against Remington, who could barely remember what had happened enough to submit a plea.

It had been a family cursed by violence and inconclusive measurement of justice. Fourteen years earlier, Richard Wheeler’s own mother, Harriet Wheeler, had been found dead behind the house where Richard lived, her head smashed in by club and boot heel. Jared Wheeler, a cousin of Richard, had been arrested and charged with her murder but was acquitted at trial. Richard Wheeler’s killer, Jared Remington, was ultimately indicted only for aggravated assault rather than murder, as evidence indicated he had acted in response to Wheeler’s initial attack. The cycle of violence in Hatfield continued in January 1894, when a man named Tom Gagle received “terrible blows to the head” at the hands of Wheelers still residing in the same shanty.

The Last Case

There were other subsequent cases — Levi Fournier, charged and acquitted of strangling his wife in Montague in 1895, and there were the allegations of corruption after a grand jury failed to indict the son of Henry Chipman Hallett (superintendent of the Belding Bros & Co. Mill in Northampton and future mayor of the city) for shooting his 14-year-old sister.

But it was the murder of Hattie Evelyn McCloud in Shelburne Falls that marked the apex of Munyan’s career, and it was the case that eventually broke him.

On January 8, 1897, George Dennison Crittenden discovered the lifeless form of his daughter, Mrs. Hattie Evelyn McCloud, along the side of Crittenden Road. Hattie, 37, the eldest daughter in a large and prominent family, had married William Lewis McCloud in 1882, but he had died eight years later, leaving her a widow. She had one known child, Alberta Dawes McCloud, and lived quietly among her parents and siblings in Shelburne Falls.

Munyan was among the first professionals called to investigate. Attention soon turned to a young man with a troubled reputation: John O’Neil Jr., a 27-year-old laborer from Charlemont, the eldest son of John O’Neil Sr. and Katherine Kelley O’Neil. Though from a large family with deep roots in Franklin County, O’Neil had long been viewed as an outsider. He lived a life on the fringes of town life: drinking heavily, frequenting stables and saloons, taking day labor when he could find it, and skirting the line of the law.

Descriptions of him in the press painted a picture of a man adrift: quarrelsome, idle, “rough,” yet without a serious criminal record. His parents and siblings lived in Buckland and Greenfield, but John Jr.’s world was smaller, his circles tighter, made up of drinking buddies and strangers.

In the days following Hattie McCloud’s murder, Detective Munyan pieced together small, scattered clues: witnesses who saw O’Neil near the crime scene; reports that he’d been seen with a roll of bills shortly afterward; a purse that matched the description of Mrs. McCloud’s; inconsistencies in O’Neil’s explanations of his movements. Munyan assembled bits and pieces into a case: a well-worn path through the snow, an opening in the stone wall near the body, tracks leading from the road to the woods.

In court, Munyan described interviewing O’Neil at the Greenfield train depot after the arrest, eliciting a rambling narrative from the young man. In his plainspoken but persistent questioning, Munyan chipped away at O’Neil’s story, allowing O’Neil to incriminate himself through omission as much as admission.

Crowds packed the Greenfield court to glimpse the July 1897 trial. It was a legal spectacle rarely seen in Franklin County: 120 witnesses called, three judges presiding, multiple stenographers taking down every word. The prosecution, led by Attorney General Knowlton and District Attorney Hammond, leaned heavily on the circumstantial case. Defense attorneys argued that reputation and suspicion had replaced hard proof.

After just 82 minutes of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree. The sentence: death by hanging. On January 7, 1898, nearly a year to the day after Mrs. McCloud’s death, O’Neil stood on the gallows addressing the witnesses, “I am innocent. I forgive everybody. May God have mercy on my soul.”

The strain and exertion of the investigation took their toll on Munyan, who would turn 60 in the fall of 1897. Having already been hit with what was described as paralytic shock in April of 1896, he was rendered homebound in January of 1897, just weeks into the O’Neil investigation. Even as the recuperating Munyan was preparing for the O’Neil trial that summer, he was delivered yet another merciless blow, when his beloved wife Hattie succumbed to pneumonia in March.

A year after O’Neil’s February 1898 execution, Munyan announced his retirement. In the intervening year, Munyan’s brother had died, and he had moved into his daughter’s home in Haydenville. Munyan’s retirement did not even hit the six-month mark: he died at the Northampton asylum in June, his death attributed to arteriosclerosis.

His obituary invoked his years of law enforcement service, his service during the Civil War and noted he “possessed a talent for music, as did all his family, and was a player and one of the leading spirits in the famous old Haydenville band.”

His funeral drew state officers, sheriffs, wardens, and deputies from across western Massachusetts, a testament to the respect he had earned among his peers. His remains were interred in Haydenville’s High Street Cemetery.

Leave a comment