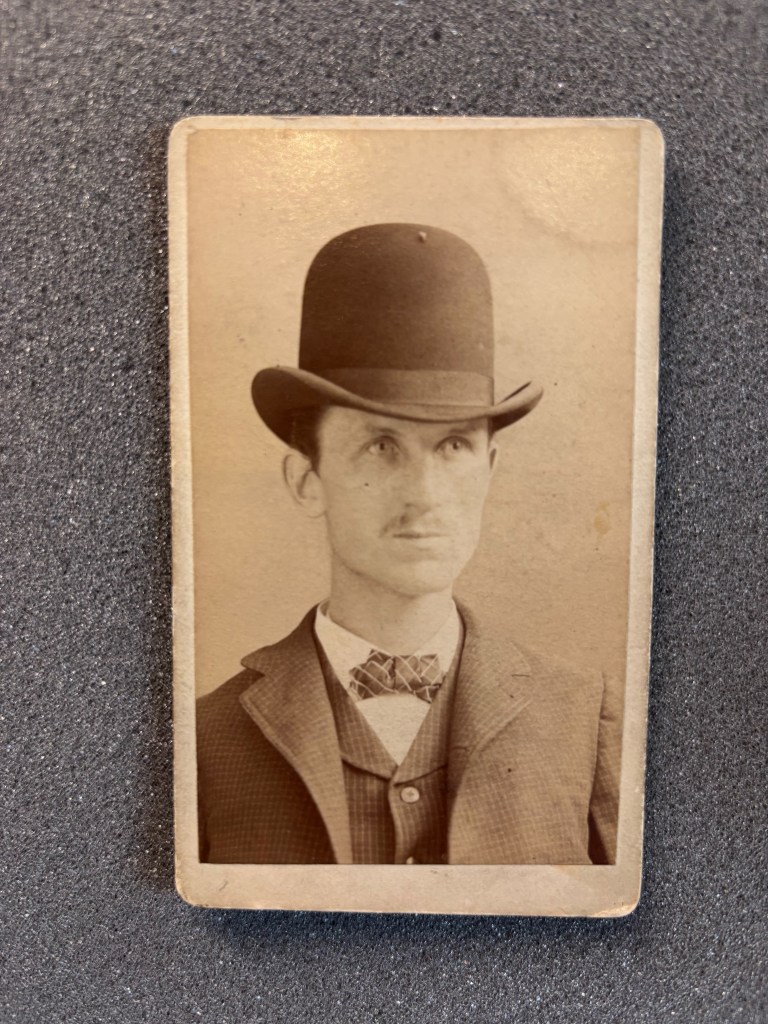

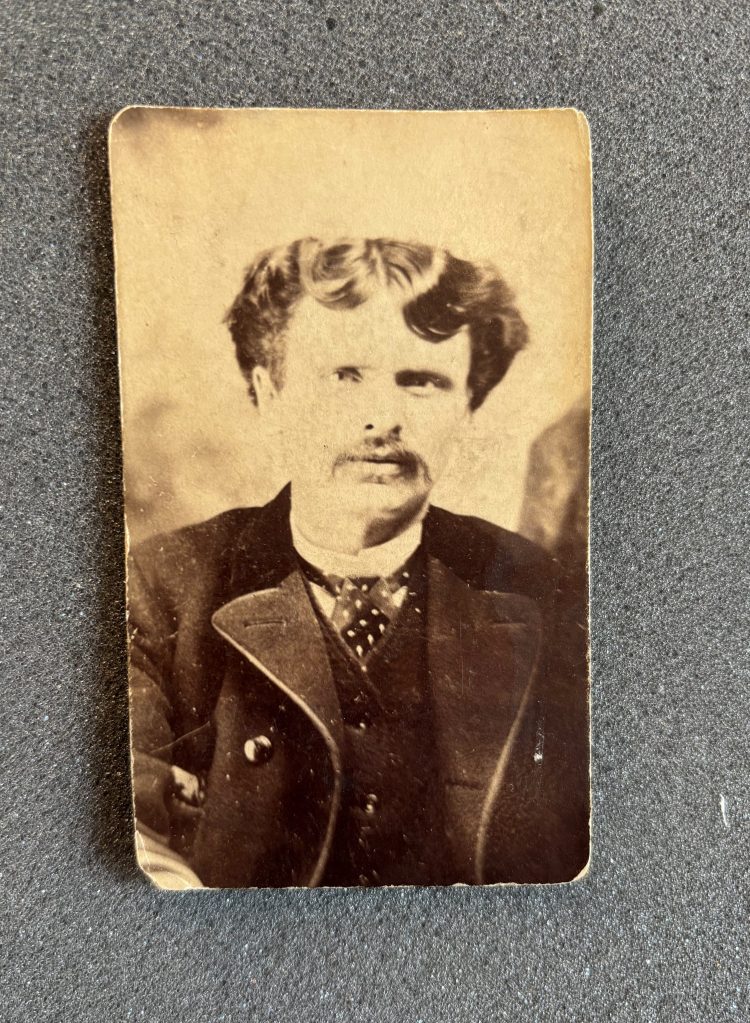

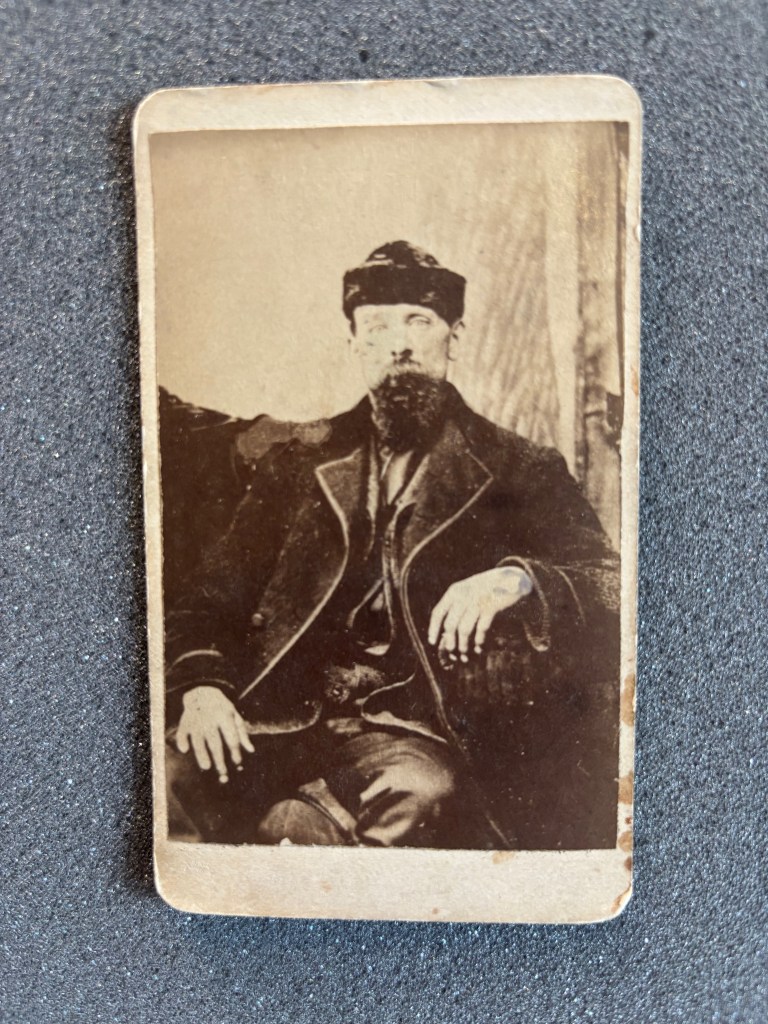

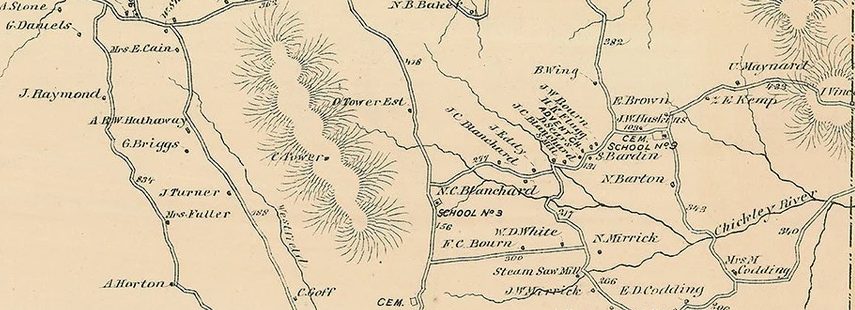

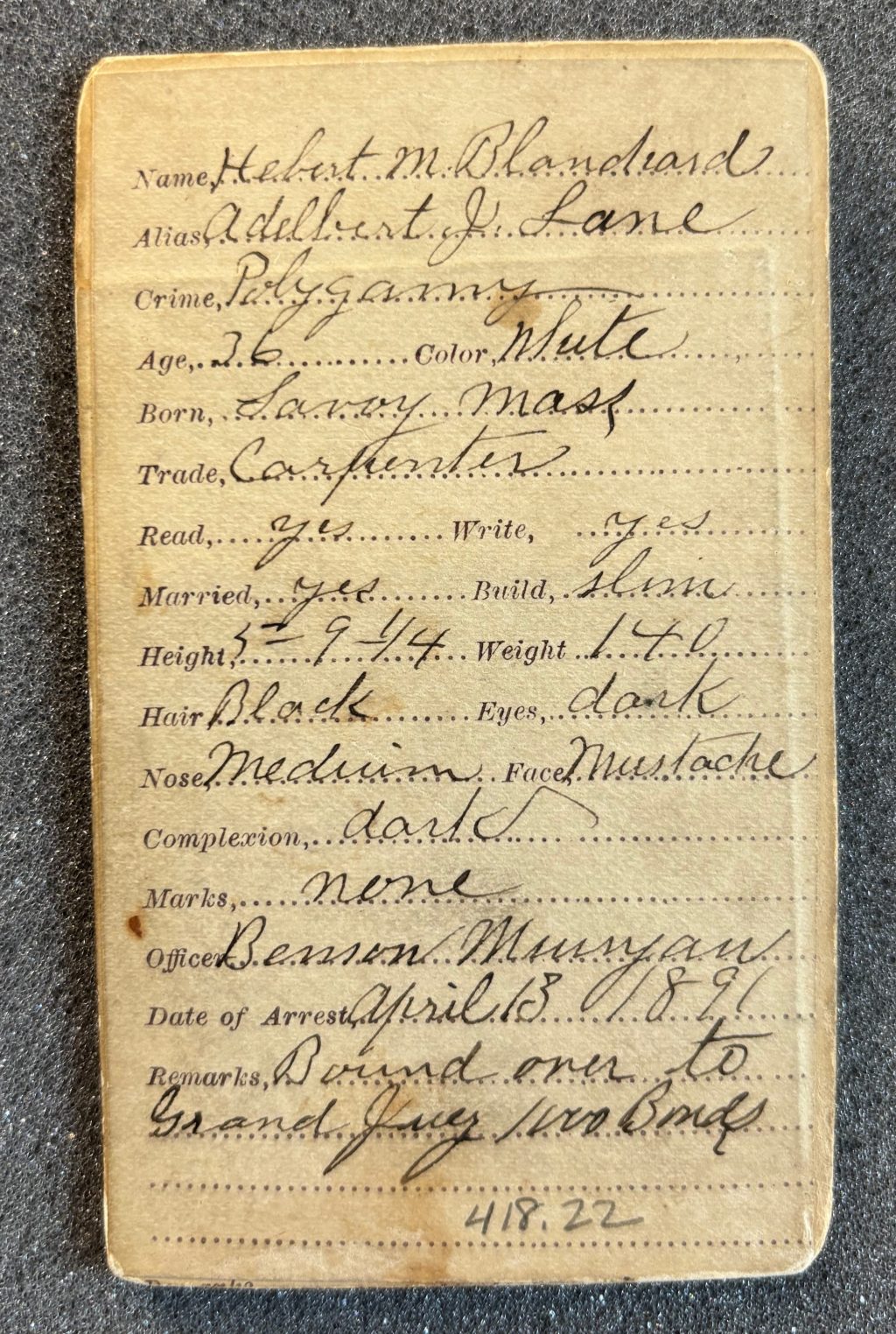

Detective Benson Munyan of Haydenville, the man who arrested my cousin Herbert M. Blanchard in 1891 for the crime of polygamy, had Herbert’s photograph taken for posterity, adding it to a substantial collection of photographs accrued during Munyan’s twenty-year career. The mugshot of Herbert Blanchard is among more than 400 surviving photographs that a descendant of the detective gave to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 2024.

An innovation of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, such collections, or “rogues galleries” were an early attempt by 19th-century police to keep a database of the criminals they pursued. The photographs—mostly cartes de visite no bigger than a baseball card—featured identifying information on the back: names, aliases, crimes charged, physical characteristics, and so forth. No more than ten of the cards in the collection identify suspects that Munyan himself arrested or investigated. Many of the cards are for cases investigated in Boston and its surrounding cities, though there are several tied to crimes in Western Massachusetts that Munyan probably had a hand in investigating.

The cards are incredibly well-preserved, except for a few examples bearing the scribbles of some anonymous descendant. So, donning blue rubber gloves, carefully sliding each photograph out of its numbered envelope, and resting it on a foam pad for viewing, I recently spent the day in Boston interacting with long-forgotten thieves, thugs, rapists and killers. Looking at Munyan’s collection provides a literal snapshot of criminality from the last two decades of the 19th century in Massachusetts.

While violent criminals are in this gallery, most of the faces that stare back at you from these carefully preserved cards are those of men—and one woman—arrested for property crimes of one fashion or another. Breaking and entering by “second story men” and other kinds of burglars are the most common crooks in the cards, as well as forgers, embezzlers, and pickpockets. Horse thieves were numerous: there are more of them in the collection than forgers, sneaks, and pickpockets combined.

The portraits come in various styles, depending on who took them. Some of the western Massachusetts portraits, marked with the names of the photographer’s studio where they sat, could be those of any swell out to impress, with a portrait featuring an inset closeup that bears more resemblance to a yearbook sitting than a mug shot.

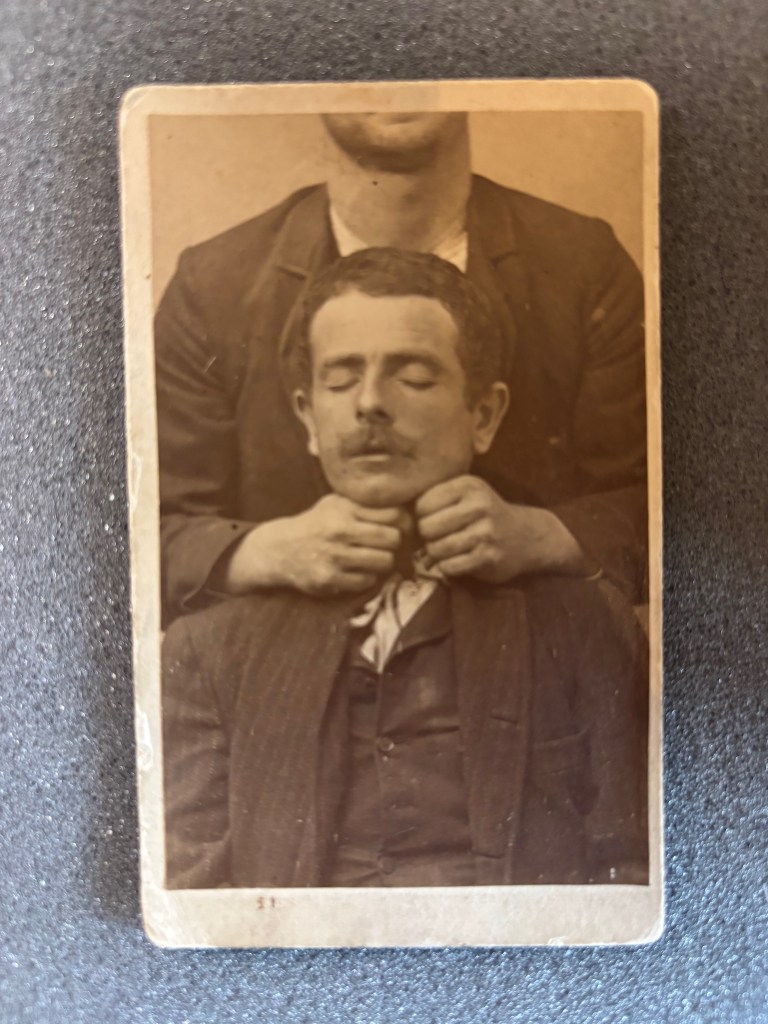

Some, like burglar William Moore, bunco man Thomas O’Brien, and James Lenehan, whose crime wasn’t written down, were less willing to sit for a portrait, and their visages are caught for posterity mid-struggle, held in a chokehold or worse, to position identifying marks for the camera.

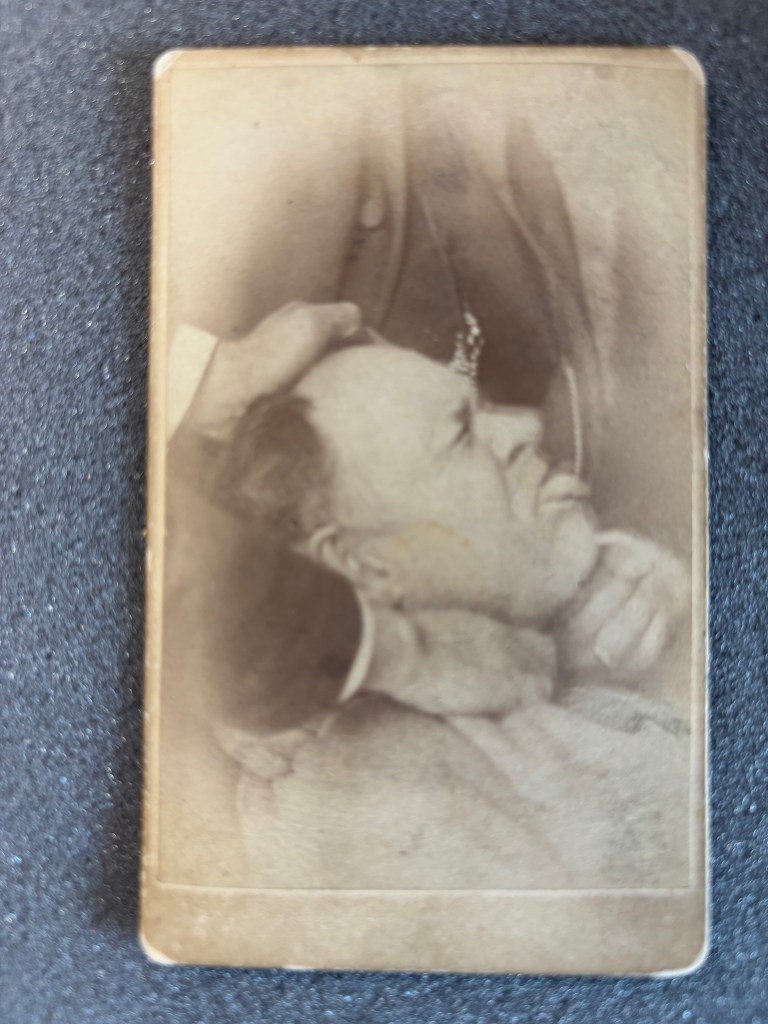

Patrick Murphy, an accused chicken thief, put up no struggle for his photo, being the only corpse in the collection. The tall, athletically built Murphy and his equally jacked brother Maurice had been acquitted of their involvement in a stabby 1889 fracas at Pittsfield’s Burbank House, but he met his end while discovered dressing a cache of stolen poultry in the woods just outside of Chatham, New York. Shot by a local, he died refusing to identify himself but was traced back to Berkshire County thanks to the postmortem photo.

There’s Emma Murray, AKA Emma Sault, nabbed in 1889 following a one-woman pickpocketing spree in Springfield, where she liked to stroll outside Forbes and Wallace and rifle through women’s pockets.

Men called till topper, bunco man, skin gambler, or rubber stamp man. Men with aliases like Ready Foss, Curly Tom, Red Riley, Ed Greenfield, Ferd L. Snowdale, Frenchy Kenny, New York Slim, Slim George, and just Fiddleneck. Men with many names, like swindler Fred Howe, who was missing part of a forefinger but who had many names to spare, including W.B. Howe, W. E. Chase, H. E. Chase, H. C. Chase, H. E. Bailey, Charles E. Bailey, and W. B. Burnham.

The gallery includes a dozen men charged with murder, many of them far afield of Munyan’s beat, but not exclusively.

There’s John J. Connelly of South Boston, aka Paddy McGrath, charged with highway robbery against one Thomas A. Lomasney on the docks in Gloucester in 1887. Connelly, a fisherman and the child of Irish immigrants, would testify that he only deprived Lomasney of a couple of cigars as the man lay in a drunken stupor, and it was his associate Thomas Smith who took the man’s watch and money. The problem was, Lomasney was found drowned, and his autopsy revealed no sign of intoxication. Smith was given a life sentence for his part, and Connelly hanged himself on October 3, 1888, while he was in a Salem lockup awaiting trial for the robbery charge, fearing murder would be added.

There is Michael Mahoney, or Michael “Jake” Whyte, who would serve a life sentence in the state prison for the August 1888 murder of East Woodstock, Connecticut farmer Frank Spencer, who was shot and deprived of $17, a pocket watch, and his suspenders in Dudley, Mass., near the state line. Arrested in Worcester, Mahoney initially denied involvement but eventually copped to the crime after investigators found Spencer’s watch in Mahoney’s possession, along with matches and a collar stained with blood.

There is the arsonist Charles S. Young, alias Warren S. Dearborn, who was sentenced to life in prison for setting a fire in West Newbury that claimed the life of a father and his son.

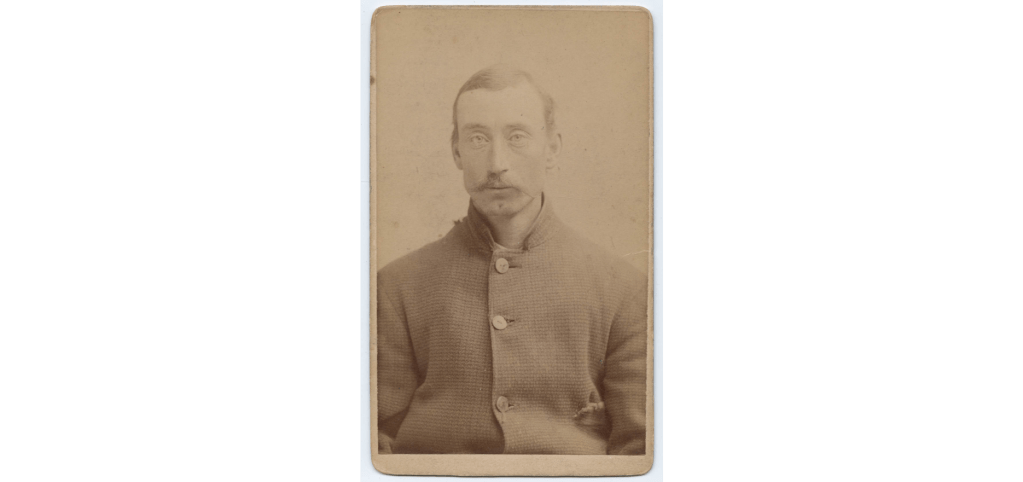

There is Peter Eno, a former Boston & Maine railroad brakeman who stood before the camera in the spring of 1892 for the murder of his wife, Mary “Minnie” Richards. Minnie was a restaurant owner, having just opened a new establishment near the corner of Broadway and Common in Lawrence, Mass., two years previous, an establishment that touted the innovation of electricity. The couple had married in 1883 and produced a son in 1885, but the marriage had been on the skids since Minnie had shown Eno the door in 1889. It turns out Eno had another wife in Connecticut: Eno had exchanged vows with Julia Doyle in Plainfield, Connecticut, a decade earlier, and was the father of two children with her. Minnie had sued Peter for non-support and had charged him with assault for past abuses. On the evening of April 5, Eno tracked Minnie down, and after a brief interaction, shot her point-blank in the head, killing her instantly.

Peter fled but was captured when he, oddly, sought shelter at the police station disguised as vagrant “Charles Little.” Initially claiming the shooting was accidental, he later confessed it was intentional. He is quoted as saying that he “realizes his unenviable position and prefers hanging to imprisonment for life.”

Three weeks later, while awaiting trial, he opted to serve as his own hangman, utilizing a noose fashioned from the bed sheet in his cell.

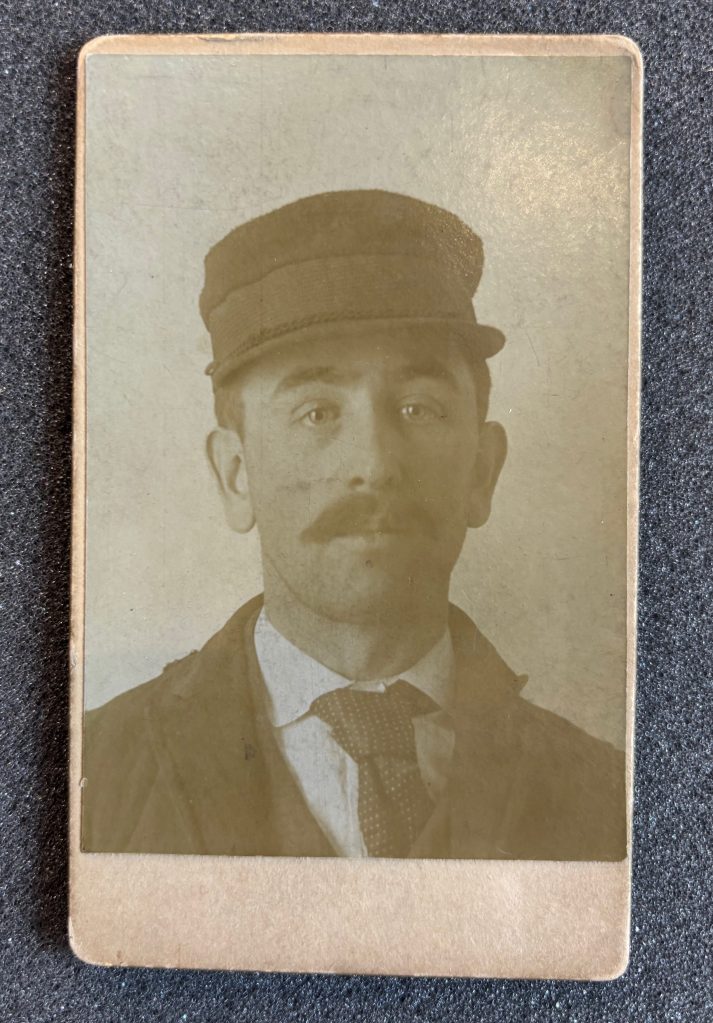

William Barrett, aka William Bassett, a fairly successful burglar who made the mistake of attempting to leave no witnesses, or at least eliminate one, while burglarizing the home of Weston farmer James H. Farrar in May 1894. According to the newspaper accounts, Farrar was awakened by noise in his bedroom around 5 o’clock in the morning and discovered Barrett burglarizing the home. Barrett was later found to have ample tools of his trade and property belonging to families in Lincoln, Mass. Farrar and his brothers gave chase when the burglars tried to hit the road, near Weston’s Cherry Brook station. Barrett shot Farrar three times in the chest to end the pursuit, and gave the farmer a killing blow to the head before Farrar’s family could disarm him.

Barrett was handed a life sentence for second-degree murder, and he would continue to claim innocence and file an appeal. Following his conviction, investigators were able to track down items from at least fifty-four burglaries he committed across southeastern Massachusetts, including a collection of rare stamps he was storing with a James S. Chaffee. It turned out Barrett/Bassett had been living a double life: for 20 years he rented a solo apartment at 22 Eliot Street in Boston, the base from which he stole some $500,000 worth of goods. Meanwhile, he lived the high life back in New York City, providing his wife there with a posh flat at 353 West 58th Street and keeping her supplied with thoroughbred horses.

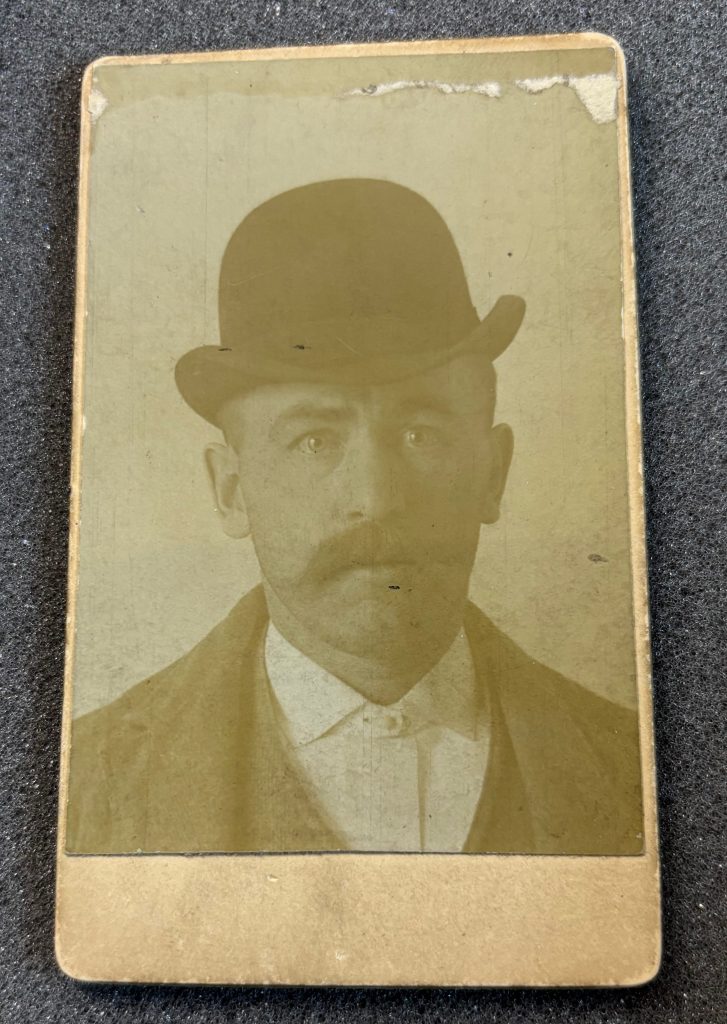

The brothers Kane, or Kain, Patrick and Thomas, were charged in the death of Michael H. Day of Stoneham, Patrick’s father-in-law. Day, who owned a piggery and collected swill for a living, supplemented his income by offering his carriage to transport factory workers to and from their jobs in nearby Reading. Day’s mood about the largely unemployed Kane brothers had been on a slow boil for some time, and the ill will between Day and the Kains exploded on the Ides of December 1894. Returning with his daughter from an evening of driving to Reading and back, the wearied Day unharnessed his horse and spied the brothers, who lived at his Oak Street property, in the yard. Day managed to summon up the energy to lay into his layabout son-in-law and Thomas, and hit Thomas over the head with his lantern. A fierce struggle ensued, and within minutes Day was dead, stabbed in the neck and face, with the killing blow rendered to his heart. Initially charged with murder, the Kane brothers pleaded not guilty by matter of self-defense. A grand jury reduced the charges to manslaughter.

The collection also contains a pair of photographs of crime victims, not in death, but simple portraits. There is Deltena Davis, whose body was pulled from the Mystic River in 1892 following a frantic two-week search. Munyan’s collection includes a photograph of William H. Smith, who was charged with aiding James A. Trefethen, his brother-in-law and Davis’s fiancé, in her murder. Both men were later acquitted, following a pair of trials that were treated second only to the trial of Lizzie Borden in the Boston Globe’s January 1894 roundup of cases from the previous year1. The other victim’s portrait is of Sophia Bessette of Ludlow, whose husband buried an axe into her head on the night after Christmas, 1889. Jean Pierre Bessette himself, who would spend the rest of his days at Bridgewater State Hospital for his deranged deed, is also in Munyan’s gallery.

If you want to have to sleep with the light on for a month,

please click the picture to check out his prison photo at Find a Grave.

To Be Continued: The Collars of Detective Munyan.

Photo Credit: All the photographs shown here were made available courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the nation’s oldest historical society, which maintains an independent research library in Boston’s Back Bay. You can now view the entire Munyan collection at the MHS website, where you can support the museum through the purchase of high-definition scans of the criminals of your choice.

- Which also includes a notorious murder case in Western Massachusetts, which I will get into for a future installment of this series. ↩︎

Leave a comment